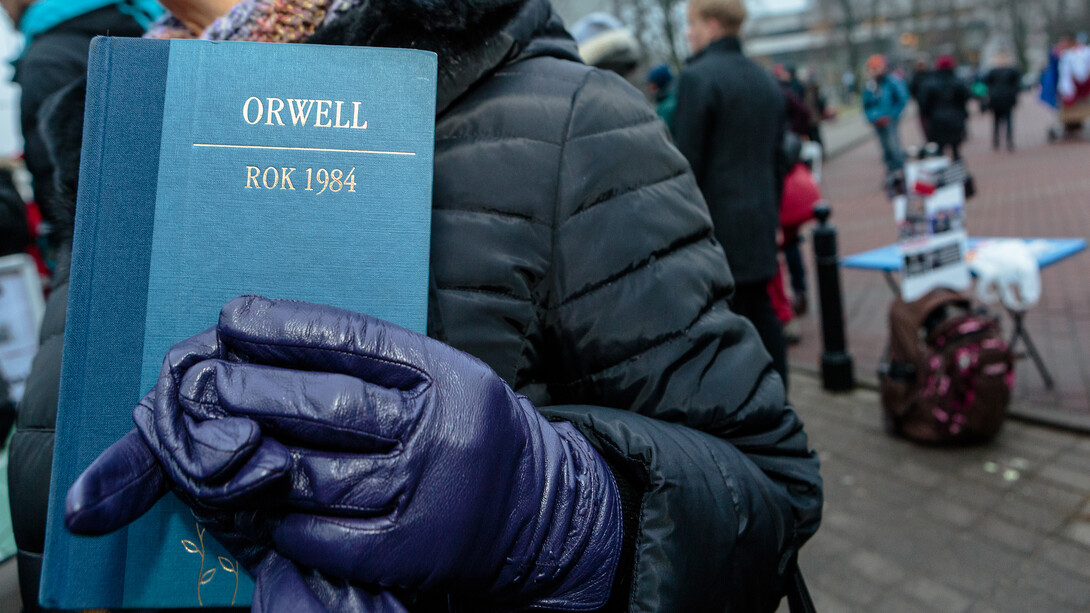

George Orwell’s novel “1984” – which depicts a grim future in which “War is Peace,” “Freedom is Slavery” and “Ignorance is Strength’’ – has gained renewed popularity.

The book has been at the top of Amazon’s bestseller lists in the United Kingdom in all versions – paperback, hardback and Kindle. In the United States, hardbound and paperback copies have been sold out. A spokesman for Signet Classics, noting “remarkably robust” sales, said it had ordered an additional press run of 75,000 copies.

Guy Reynolds, an English professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, is particularly interested in the recent sales surge for Orwell’s dystopian masterpiece. In a bit of serendipity, he included “1984” in the curriculum for his new freshman honors course on post-war British literature to be launched in the fall.

Reynolds said a 75,000-copy press run is practically unheard of for a book that’s been on the market for nearly 70 years. For comparison, Reynolds, who is general editor of scholarly editions for Willa Cather’s works, said a new student edition of a major novel might have a press run of 10,000 copies. He would expect it to take four to five years to sell that many copies.

Many observers credit the “1984” spike in sales to the “alternative facts” – as described by President Trump’s adviser, Kellyanne Conway – arising after the inauguration.

Reynolds, however, chose the book for his new course long before Trump was elected president. While Trump’s actions as president appear to have spurred interest in “1984,” Reynolds says the novel has long stood as a warning against the recurrent danger of autocracy.

“It’s a book about propaganda, information and the control of information,” he said. “Some of the technology in the book is very cleverly deployed.”

A staple of high school and college literature courses, “1984” had long been viewed as an allegory about the dangers posed by the Soviet Union and other totalitarian regimes of the mid-20th century.

The course of history left those concerns behind. Reynolds said students today might detect echoes of Orwell in reality TV and internet tracking of their whereabouts and buying habits – Orwell described a “telescreen” that monitored the protagonist’s movements; or in media reports that are tailored to its audiences’ political biases – that’s the “Ministry of Truth;” or even in the vicious accusations leveled at political candidates – that’s the “two minutes hate.”

“Orwell got a lot of things curiously right,” Reynolds said. “People have been able to see, for 10 or 15 years now, just how Orwell seems to have got hold of a certain vision of how our world might develop.”

Orwell worked as a propagandist during World War II and had a keen understanding of how people could be manipulated through information, Reynolds said. Some might rightly dismiss “1984” comparisons as hyperbole, Reynolds said. A robust media, First Amendment rights and multiple centers of power all are checks against the all-controlling government depicted in the novel.

Reynolds said he first read “1984,” Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” and Anthony Burgess’s “A Clockwork Orange” in a two-year span when he was 12 and 13 years old, growing up in Manchester, England. He said he’s eager to see how his students respond to the book and what analogies they may draw between the world of “1984” and the world of today.

“Some students may conclude that this is really just a novel about the Soviet Union, totalitarianism and the mid-20th century European scene and that it’s a stretch to draw parallel’s between Orwell’s ‘1984’ England and (today),” Reynolds said. “I can see some of those points and that’s a legitimate point of view. But I suspect others will bring to the class a desire to investigate and debate parallels between Orwell’s world and the one they might one day be living in.”