A growing number of Nebraska school districts are sourcing ingredients for their school meals from local farmers.

In a state like Nebraska, that makes sense, said Jordan Rasmussen, an Extension educator with Rural Prosperity Nebraska. But as much as the farm-to-school movement is a logical extension of the state’s robust ag economy, it’s also a holistic approach to improving Nebraska’s communities.

“Not only does it address a community’s physical health, but also economic, educational and social health,” Rasmussen said.

Hosted jointly with Nebraska Extension, the Nebraska Department of Education’s annual Farm-to-School Institute trains communities on the logistics of farm-to-school programs. Workshops, lectures and seminars not only help connect schools with producers, but focus on goals, action plans and grant opportunities.

Jay Wolff, co-owner of Wolff Farms Produce in Norfolk, attended the institute during the pandemic.

“The training helped in filling out (bids for larger schools),” he said. “They also talked about insurance requirements, food safety requirements. We did a little bit of sales to schools before the training, but it really helped out a lot after.”

While knowing the ins and outs is important, the heart of farm-to-school centers on Nebraskans.

In the cafeteria

The cafeteria is where farm-to-school is most apparent. Working with Rasmussen and fellow Extension Educator Kayla Hinrichs, Burwell Public Schools recently received two U.S. Department of Agriculture grants of nearly $130,000, which allowed them to replace and upgrade kitchen equipment. Pius X High School in Lincoln, which also attended the institute, used grant funds to purchase immersion blenders and make other upgrades to their kitchen, allowing them to process and store the produce that comes in abundance in autumn.

“During the fall, we’ll get lots of tomatoes,” Carmen Goeden, Pius X’s director of nutrition services, said. “We can’t go through all of those tomatoes fresh, so we’ve learned to process them. We’ll blend them, and then freeze them and use them for sauces or soups.”

Burwell and Pius X have also received the Nebraska Department of Education’s Local and Indigenous Foods Training grant, which brings Extension educators into schools to teach about the benefits of local foods. Hinrichs calls these visits the “Chef’s Table,” where she has made roasted turnips and Moroccan meatballs with students. Recently, Pius X taste-tested bison pizza.

“Ultimately, we want students to eat a variety of healthy foods,” Hinrichs said. “If they’re exposed to them in school, I think that’s a great start to building good nutrition throughout their life.”

But it goes beyond produce, Goeden said. After connecting with producers through the institute, Pius X has embraced introducing children to healthy foods by serving eggs from local growers, as well as cheese from Jisa Farmstead in Brainard, and whole grain breads from Rotella Bakery and milk from Hiland Dairy, both in Omaha.

In the classroom

While some schools bolster their menus from local sources, others serve produce grown on their own grounds. At Southern High School in Wymore, Brady Meyer teaches an agriculture education class in which students grow produce in a greenhouse and with hydroponic towers.

“We’ve got a bunch of peppers out there right now that we’re going to harvest at the end of the week, and the kids are going to make a salsa,” Meyer said.

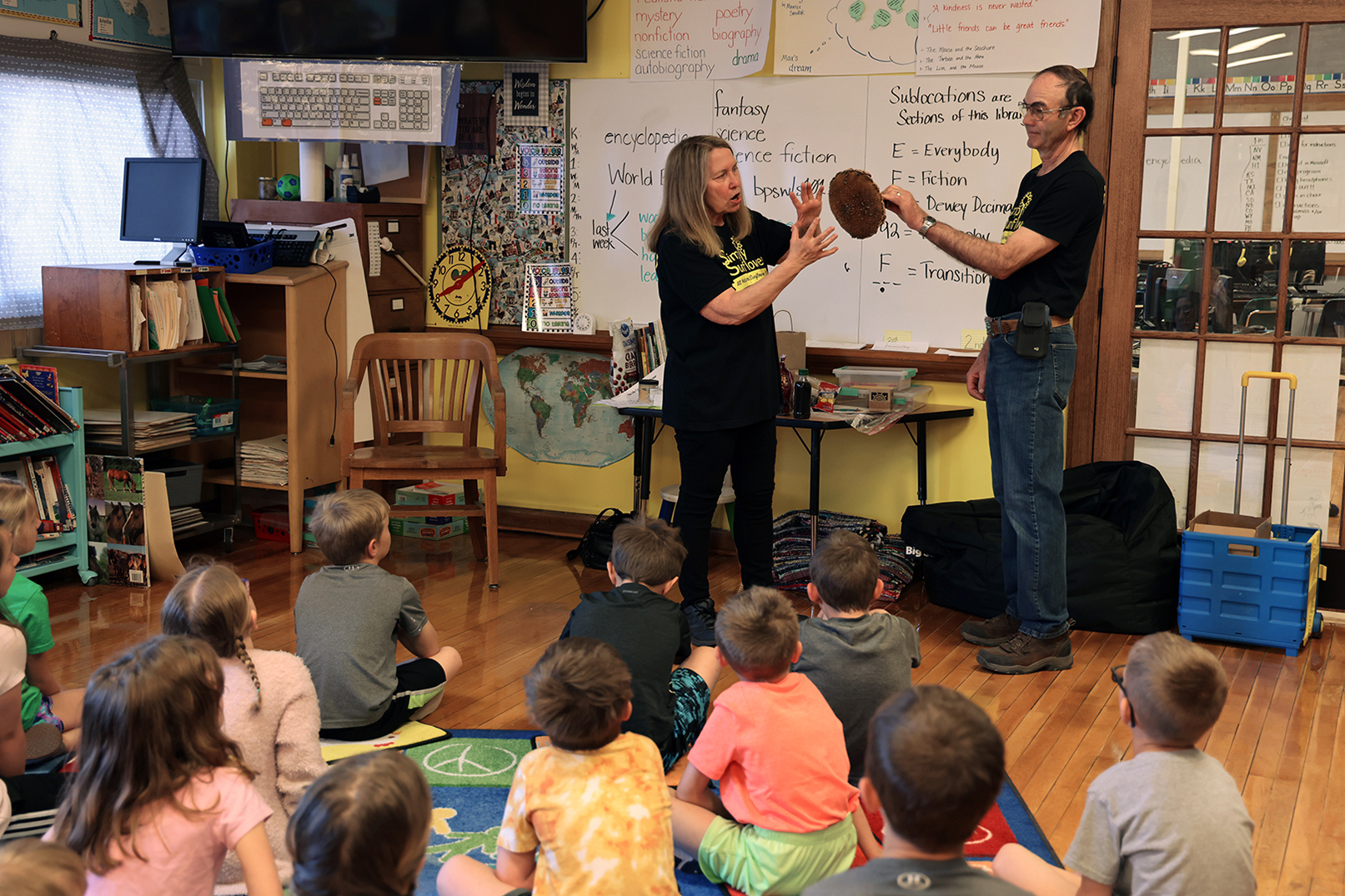

Classes such as these help students step away from the theory and engage in the practice. In Burwell, high school students visited Trotter’s Garden Shoppe and Learning Center in Litchfield, where they harvested produce. Recently, Alan and Jeanette Koelling, owners of Simply Sunflower farms, presented on the sunflower oil-making process to Burwell Elementary School students. And at Overton Public Schools, Julie Loudon, an agriculture educator, uses ag-centered object lessons in pre-existing classroom curriculum.

“It’s just being a little bit more purposeful about connecting the things we already teach to the cafeteria,” she said. “That’s the most tangible place for food for kids. That’s the first connection from cafeteria back to the classroom.”

In Macy, farm-to-school at Umónhon Nation Public School focuses on students’ connection to food and food’s connection to community. Delberta Frazier and Brenda Murphy teach the Let’s Go Outside program, which includes in-class lessons and hands-on experiences.

“We grew a lot of carrots and radishes, parsley and lettuce,” Frazier said. “We grew tomatoes and taught students about artificial pollination, so the kids did the pollinating.”

Part of the program also includes helping students connect with their language and culture. For one lesson, students dry and bottle herbs, label them with their scientific and Indigenous names, and report on how the herbs can be used for food and medicine.

Ted Hibbeler, the Native American engagement coordinator for Rural Prosperity Nebraska, said the Umónhon Nation Public School students give the produce they grow directly to families in the community and to the school’s lunch program.

In the community

Farm-to-school serves another purpose beyond students. It supports local businesses and keeps money in the local economy.

“Keeping that money here in Nebraska is huge,” said Mark Roh, owner of Abie Vegetable People and co-owner of Lone Tree Foods, a produce distributor to schools in the Lincoln and Omaha metro areas. “Those are the end goals for the local food movement — not just one-off sales, but can farms and families start to design how we cash-flow our entire year on (programs) like this?”

Farm-to-school also presents opportunities for smaller farms, said Gary Fehr, owner of Green School Farms in Raymond. With only one acre dedicated to produce, Fehr works with about six small schools per year.

To expand statewide, Fehr believes Nebraska’s farm-to-school movement will require investments in infrastructure to help farmers with processing and storing.

“That’s a huge topic in the local farms community,” Fehr said. “Can we get some shared infrastructure in place, where we can take a butternut squash to a certified kitchen, dice it up, freeze it and then offer that to schools? But that’s a whole different industry and enterprise.”

Even so, it’s a conversation Nebraskans are already having. In 2017, the Nebraska Department of Education hired Sarah Smith as the first farm-to-school coordinator. In 2022, the state legislature passed LB396, the Adopt the Nebraska Farm-to-School Program Act, which provided funding opportunities specifically for schools and farmers involved in farm-to-school.

“This is an exciting time for the farm-to-school movement in Nebraska,” Fehr said. “It’s kind of taking it from the one-on-one grassroots level and expanding it to get a lot broader participation.”

Logistics aside, farm-to-school is already having an impact on communities across the state, Rasmussen said. She believes that as the programs grow, Nebraska will benefit.

“It’s not a magic wand, where all of a sudden we’re going to eat 100% fruits and vegetables,” she said. “Farm-to-school programs aim at the fundamentals. If students are starting their day with a belly full of good, nutritious food, as opposed to junk food, it makes a big difference in how those students perform in the classroom, on the athletic field and in life in general.”

[Learn more about farm-to-school programs in Nebraska.](https://foodsystems.unl.edu/farm-to-school](https://foodsystems.unl.edu/farm-to-school).