On April 23, 1909, the Omaha Daily Bee reported on its front page that “all inhabitants of several Armenian villages and towns have been killed … victims number ten thousand.”

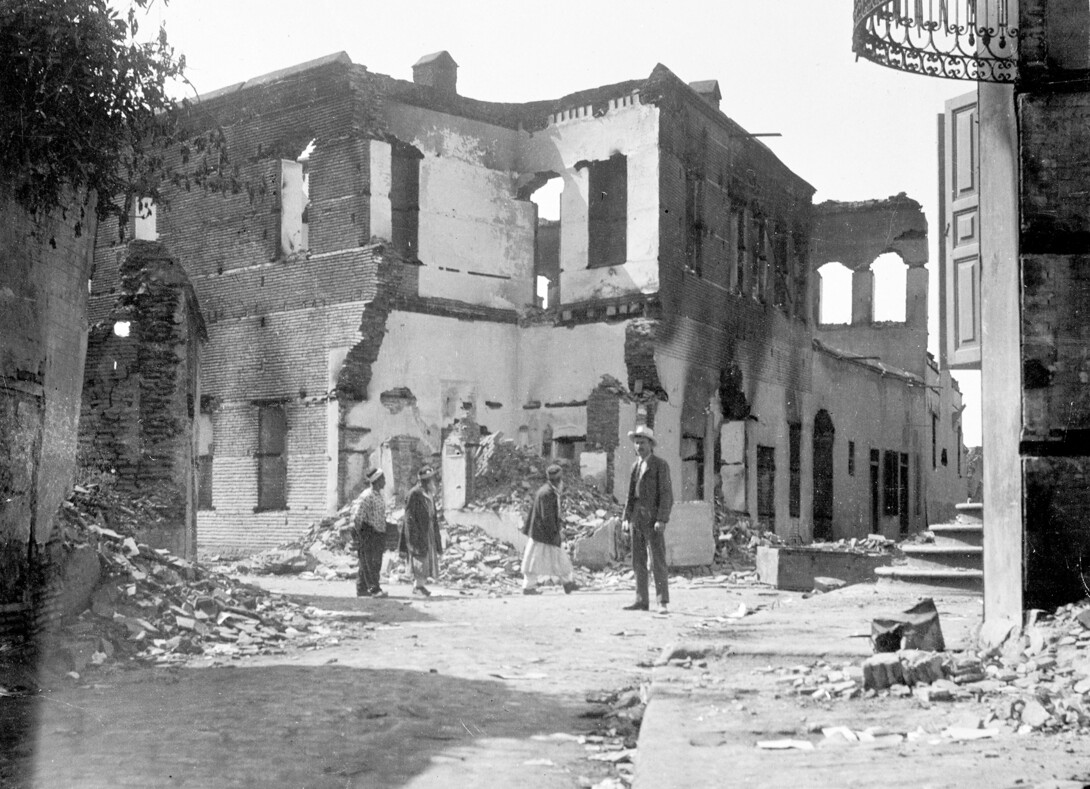

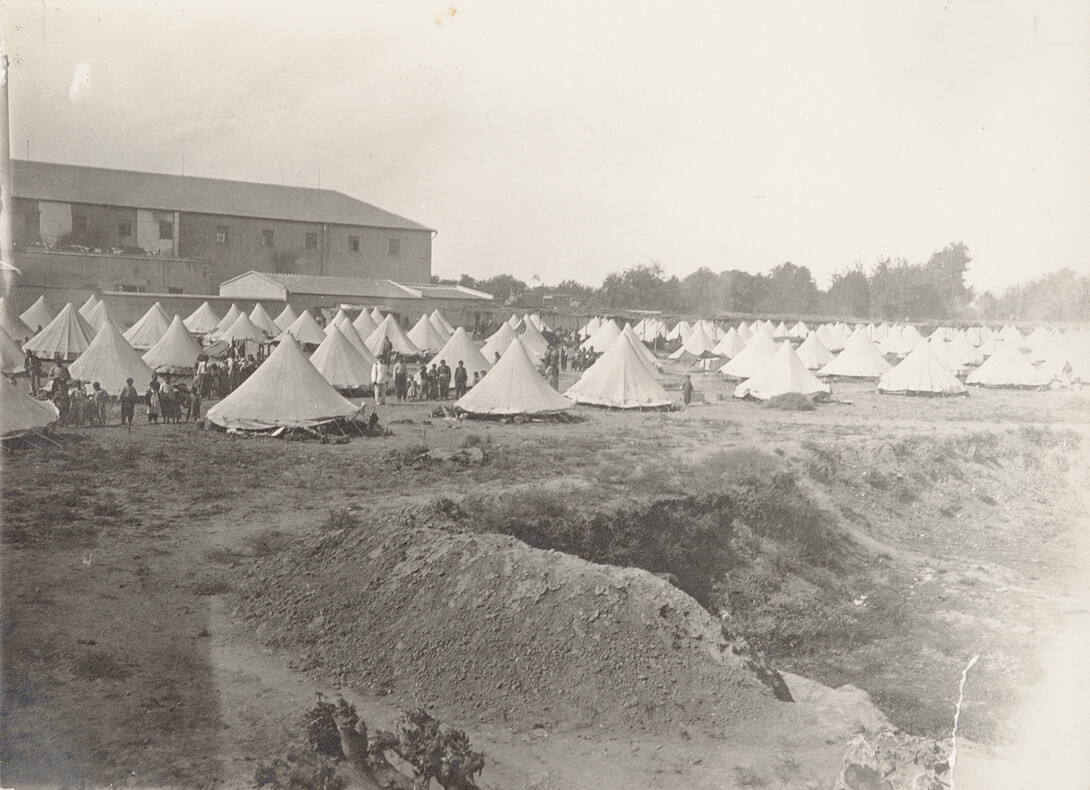

The newspaper was referring to the shocking massacres that engulfed Adana in April 1909. These massacres were twin eruptions of violence that claimed the lives of at least 20,000 Armenians and 2,000 Muslims in the former Ottoman Empire, presently Turkey.

At the time, these massacres were covered extensively by the press; however, they soon fell into oblivion. Historians tend to concentrate more on the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1923 which killed up to 1. 5 million Armenians.

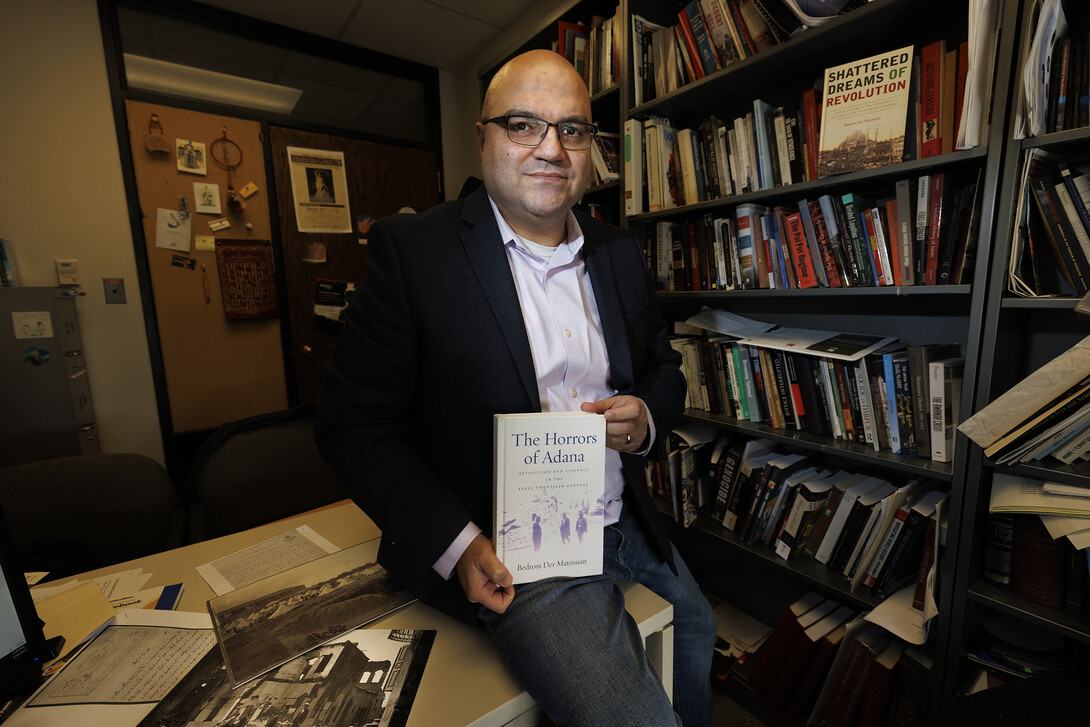

But a new book by University of Nebraska–Lincoln historian and preeminent scholar of ethnic violence in the Ottoman Empire, Bedross Der Matossian, sheds light on the Adana massacres and the political, economic and societal factors that led up to it. The book, “The Horrors of Adana: Revolution and Violence in the Early 20th Century,” offers one of the first close examinations of the events that led to the massacres. It will be published March 15 by Stanford University Press.

Relying on documents and newspapers from 15 archives in a dozen different languages from around the world, Der Matossian examines the events from the perspectives of victims, perpetrators, bystanders and humanitarians.

“It was a period where massive violence shook the province,” Der Matossian, Hymen Rosenberg Associate Professor of Judaic Studies and history, said. “The historiography of the Adana massacres has been represented in a superficial way — as Muslims killing Christians. I argue that that’s not the case. I argue that we have to really go into depth in order to understand why these massacres took place. As historians, we have to really understand and explain why phases of violence erupt in a specific period of time and lead to a cataclysm of violence.”

“In order to fully understand the Adana violence, we have to really understand the political and socio-economic structure of the province of Adana.”

The book follows his examination of the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 in “Shattered Dreams of Revolution: From Liberty to Violence in the Late Ottoman Empire,” and begins with the economic hardships wrought for some by the invention of the cotton gin and other new technologies. Previously, cotton grown in the region had been harvested by 70-80,000 migrant workers.

“The requirement for labor started decreasing with the development of new technology,” Der Matossian said. “Armenians played an important role in the introduction of this new technology of cotton machines, and there’s anger and envy towards perceived Armenian superiority in the economic sphere. Economic changes created a kind of resettlement.”

Also playing a role in the massacres was the despotic government in power, which fomented rumors and conspiracy theories. Adana was under extensive surveillance by the government before the 1908 revolution because a small group of Armenians had formed revolutionary groups in order to fight against the depredations and persecutions suffered in the eastern provinces.

“Post-1908 revolution, the conspiracies about the intentions of the Armenians were spread very fast by discontented elements of the province leading to an exacerbation of an already contentious situation.” Der Matossian said. “The government and the local notables in power now believed that Armenians were preparing an uprising in order to reinstate the kingdom of Cilicia.”

Der Matossian, who is the grandson of Armenian genocide survivors, said it is important to grow the historical knowledge of these massacres, as history has a way of repeating itself.

“Massacre is an extremely important thing that needs to be analyzed,” he said. “I argue in the book that massacre is not an aberration. It is a logical process that has its unique dynamics and has an evolution and a conclusion.”

“They are endemic to urban centers — they start there and spread — but they are not endemic to specific religions, cultures or societies.”

And, he does not want these massacres to be forgotten.

“I also wrote this book because in the field of Middle Eastern Studies, in the field of Ottoman and Turkish Studies, this important phase is not even in the footnotes,” Der Matossian said. “Most scholarship tends to concentrate on the Armenian genocide because of its magnitude and bypasses this important episode. I’ve tried to lay out here the complexity of the situation and what we can learn from this specific episode.

“What types of measures can we take? Because these massacres not only happened in 1909, similar dynamics and similar actors played important roles in different massacres across the course of the 20th century.”

Der Matossian concludes his book by comparing the Adana Massacres to the 1905 Pogroms of Odessa (Ukraine) and the Sikh Massacres of 1984 (India).