Ellen Ochoa vividly remembers some of her final moments in outer space.

They came in 2002 at the end of a 12-day mission during which Ochoa, NASA’s first Latina astronaut, helped construct the International Space Station, a large spacecraft that’s been orbiting Earth since 2000.

Ochoa and six crew members were preparing to depart the ISS, leaving behind three colleagues who would continue building the station’s laboratory. Ochoa, having logged four shuttle missions and nearly 1,000 hours in space during her career and with opportunities in leadership and administration ahead, knew she was likely experiencing microgravity for the last time.

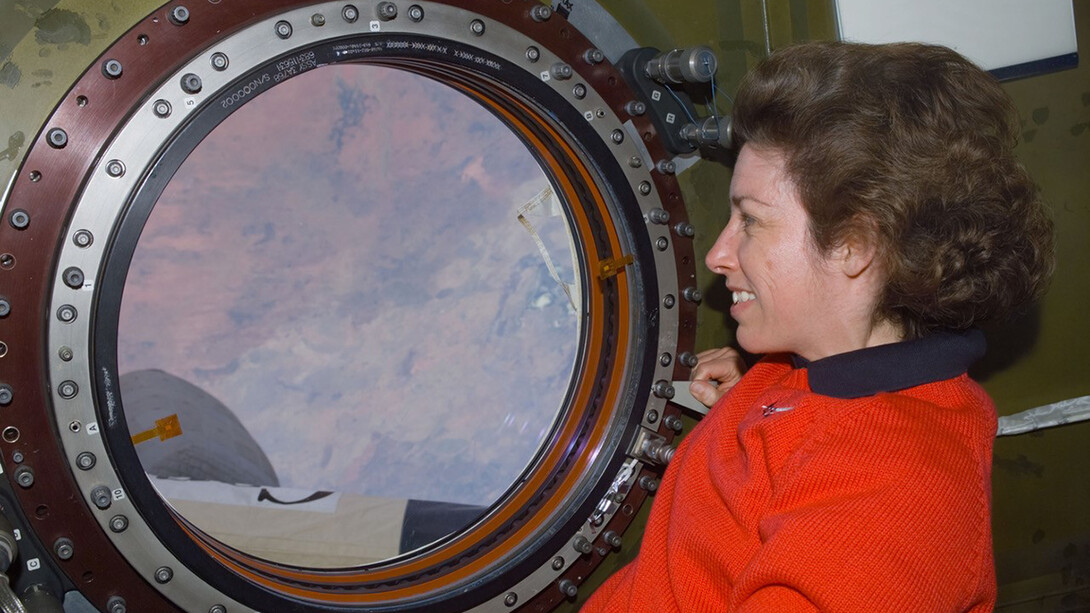

Backing away from the ISS, she could see Earth lurking behind the station. It was still nighttime there, and Ochoa could see an aurora – the brilliant light shows in the sky often called northern or southern lights – dancing along Earth.

“There were green strands and red filaments,” Ochoa said. “I never in my life thought I’d be in the position to see that, to be part of this amazing endeavor.”

Ochoa chronicled some of the experiences that brought her to that moment during a virtual keynote address delivered Nov. 5 to mark the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Women in Research Day. The event, co-sponsored by the Office of Research and Economic Development and the Association of Women in Science, was part of Nebraska Research Days, the university’s annual celebration of research, scholarly and creative activity.

About 115 people tuned in to Ochoa’s talk, “Celebrating Women in Science,” where she discussed her path to NASA and how the challenges she faced shaped her experiences as an astronaut and as the first Latinx, and second female, to direct NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. She served in that role from 2013 until her retirement in 2018, and today chairs the National Science Board, which governs the National Science Foundation and provides independent advice on the United State’s engineering enterprise.

Ochoa highlighted some of the bumps in the road she’s faced during her science career. When she started college at San Diego State University, she was unsure of what to major in. Because she was interested in math and science, she went to talk to a professor who advised electrical engineering students.

“He wasn’t at all interested in having me in his department and didn’t tell me anything about engineering,” Ochoa said.

Undeterred, Ochoa went to a physics professor for further advice. She received a much warmer reception – the professor described different careers that could stem from a physics degree. Inspired, Ochoa majored in physics, then went to Stanford University for her master’s and doctorate degrees in electrical engineering.

At Stanford, she encountered another professor who said he’d never pass a woman in the doctoral program. Ochoa not only passed, but thrived because of the rich relationships she developed with fellow classmates and faculty – most of whom were men.

“One of the things I’d like to point out is that people who were discouraging me didn’t actually know me at all; I just didn’t fit their view of what a scientist or an engineer looks like,” she said. “People who supported me were people who had gotten to know me a little bit and had a dedication and interest in what I was doing.”

Ochoa encouraged aspiring scientists facing similar roadblocks to cultivate supportive relationships and seek help through organizations like AWIS, which provides resources and mentoring to female students.

“If you do hear negative comments or feel like you’re up against a brick wall, turn to things like AWIS or people you’ve gotten to know through classes to ask questions and work through barriers.”

After graduating from Stanford, Ochoa applied to NASA. In 1981, during her first year in graduate school, she’d seen the first spaceflight of NASA’s Space Shuttle program take off. In 1983, Ochoa watched as Sally Ride – who was also a former physics major and a Stanford alumna – became the first American woman in space. Those moments were turning points for Ochoa, who became set on pursuing a career as an astronaut.

An initial rejection from NASA didn’t change her mind – she continued her research on optical systems and earned a private pilot’s license to strengthen her resume. NASA selected her as an astronaut in 1990, and her service on the nine-day STS-56 mission aboard the Discovery shuttle in 1993 marked the first time a Latina went to space.

Ochoa talked about the thrills of space travel, narrating a video documenting the STS-110 space mission to the ISS. She described the 8.5-minute trip into space at 17,500 miles per hour; discussed how she controlled a robotic arm of the shuttle in order to build one of the structural backbones of the ISS; and showed photos of her colleagues flipping and exercising in space. She also highlighted the contributions of fellow astronauts Kathleen Rubins, Kjell Lindgren, Scott Kelly and Joseph Acaba.

After four missions, Ochoa said she knew it was time to let new astronauts have the opportunity to travel to space and for her to contribute in a different way. She took on a variety of management and leadership roles, culminating in her six-year tenure as leader of the Johnson Space Center. In all of her roles, she’s remained committed to helping women and other minorities succeed in science — not for the sake of diversity itself, but because she believes it enriches the STEM fields and paves the way for groundbreaking discoveries.

“I’ve really worked on innovation and inclusion, and bringing in a diverse workforce and helping everyone feel respected and valued and included,” Ochoa said. “That is important because it helps us solve challenges, and it increases safety because people will speak up and ask questions when they know they’ll be listened to.”