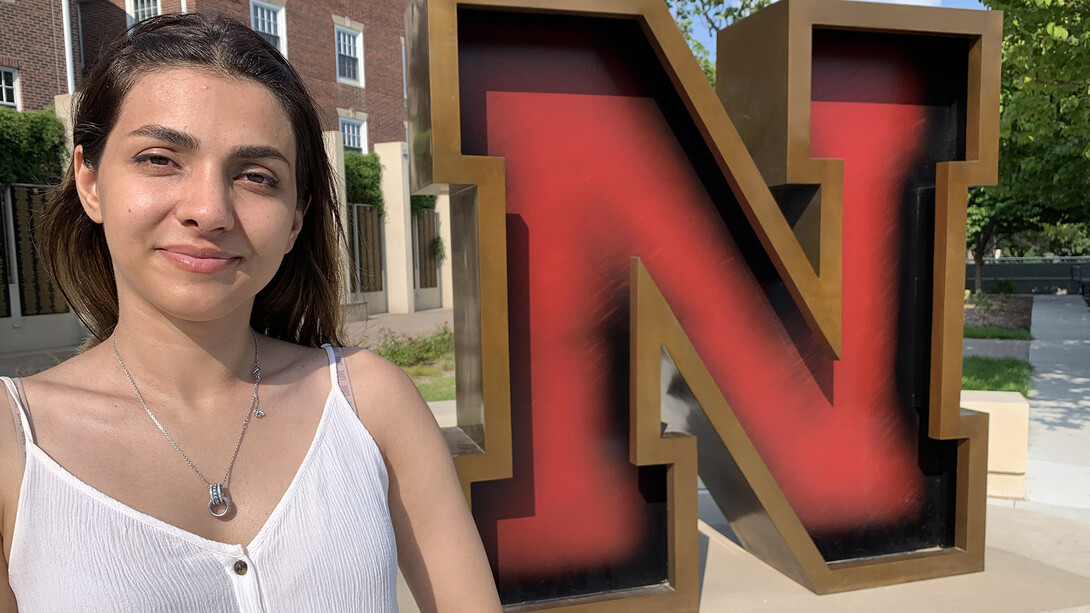

Nasrin Nawa, 27, arrived in Lincoln Aug. 13 from her home in Kabul, Afghanistan, to pursue a Fulbright Scholarship at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

A journalist who previously worked for BBC Persian and in the administrative office of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, Nawa has spent much of her first days in the United States giving press interviews. This after her Aug. 16 Washington Post column describing the dire circumstances facing her 24-year-old sister and others who have been unable to flee the country after Kabul fell to the Taliban.

As she balances worries about home with starting her first semester at Nebraska, Nawa made time for this interview in the Nebraska Union on Aug. 18.

What is the latest information about your family? Are they safe?

It’s now night there and they are sleeping. I am constantly in contact with them, I try not to sleep at night so I can live according to Afghanistan’s time and check on them. They are terrified. When I last spoke with them, about four hours ago, my younger sister showed me a video of our neighbor, who was taken away by the Taliban. They had big guns and they entered the house. We don’t know what happened after that. She was just worried: ‘What if they enter our house?’

In your column in the Washington Post, you describe your sister’s failed attempt to evacuate. Has she found an escape route?

I’ve told her to go to our aunt’s home, where it will be easier to remain unnoticed. But my aunt has no space because family friends from Herat city, which fell 10 days ago, have taken refuge there. Other avenues she’s learned about are difficult for her because they will not take our parents, too, and she does not want to leave them alone.

Nasrin Nawa left Kabul, and her sister is still there. She joins @GeoffRBennett with her story:

"It all happened in a glance" pic.twitter.com/MvA3AY3ulj— Katy Tur Reports (@KatyOnMSNBC) August 17, 2021

Could you describe your family? How long have they lived in Kabul?

I was about two years old when the Taliban took power in 1996. We fled to Iran as migrants. After the U.S. invaded Afghanistan and the collapse of the Taliban regime, we came back to our own country. With so many hopes, we started a new life there. We lived in Herat city, which is in the west of Afghanistan in the neighborhood of Iran. I went to Kabul city, the capital, when I got admission from Kabul University, the biggest university in Afghanistan. My sister also moved to Kabul to attend university. My parents came to Kabul after my father was stopped by some Taliban when he traveled to our village after my grandfather died. They were trying to impose Taliban rules and told him ‘if you don’t go to mosque every day, we will do something with you.” My father was terrified and he fled to Kabul.

Do you remember anything about Afghanistan before the American invasion and occupation?

I remember when we were coming back to Afghanistan from Iran. Everything was so flat. Everything was made of soil. There were no modern apartment buildings, just houses, and all of them were damaged. It was so difficult for my sister and I to believe we were going to live in such a place. But we were happy. People were telling us “Now you have a land, now you have a country. You can gain anything you want in your life.’

As a female in Afghanistan, did you have adequate access to education?

Actually I was deported from a school when I was in Iran because I was an Afghan. I was about six years old. I remember they called my dad. They gave him my documentation and told us to get out. I was crying. I remember it was a rainy day and my dad had an umbrella. I was asking him, “please tell me what happened. I did nothing bad. My teacher was praising me.’ He was just silent. After that, my father tried to go to Turkey, illegally, and to Europe. It never happened. We were deported three times back to Iran and once to Afghanistan – and it was war there, so my father did his best not to enter that land. In Iran, he was just a laborer, not able to pay for my studies, but he did too much to register me in a school where we paid for my studies. In Iran, we didn’t have enough rice, it was so difficult to live there. I was happy I could study in my home country. That was the most happy thing that happened to me.

Why did you decide to write about your family’s plight for the Washington Post?

Actually, it was not me that decided that. I just tweeted about it and my tweet got very much engagement. The Washington Post invited me to write it for them. Some other outlets and channels approached me because of my tweet. I was doing interviews until 9:30 p.m. Tuesday, with American outlets, the BBC, ITV out of Great Britain, outlets from Algeria and India, ABC, NBC, CNN, so many, I can’t remember.

Does going public create a risk for your family?

Yes, I am worried about that. But I have no other way. I don’t want to be silent because of the Afghan girls who have no voice right now. My sister asked me “don’t talk too much, please don’t use my name.” I am considering all of their concerns and I will be careful. It will be dangerous for them but I think someone should talk and the world should hear.

Have you always wanted to be a journalist?

I wanted to become a psychologist. My bachelor’s degree is in psychology. I wanted to help people to have a better life, a better mental life. But in our culture, it’s not accepted. I looked for ways to bring that change, to have influence on a bigger scale and I decided media is the right tool. During my fourth semester at Kabul University, I started producing a psychology show on a TV channel. After seven months, another prominent TV channel called me to work with them. I was producer and presenter for a two-hour live morning show. My life changed with that. I found a huge network. I started in the media communications department in the administrative office of President Ashraf Ghani, who recently fled under the advance of the Taliban. I decided I didn’t want to be a governmental person, sitting on a chair, so I applied to BBC and started my job as a multimedia journalist at BBC, I was working with the BBC Persian TV channel, reporting live from Kabul and recorded.

Isn’t journalism a risky profession for women in Kabul?

Being a journalist is a dangerous profession in Afghanistan. When you are a woman, it was double the risk. I was used to go to so many risky places. I reported from places where war was ongoing, explosions happened, people had just died. So many bad scenes – let’s just forget it. In a year, we lost 12 journalists who were shot, in targeted fashion, close to their homes. But I loved my job. I was satisfied I was doing something and I really loved to be an inspiring girl for other girls.

Why did you decide to do a Fulbright?

It was my whole lifetime dream from when I was in the 9th grade. I heard about it from some family and friends who told me “there is this scholarship called the Fulbright, that is the best scholarship in the world, the most prestigious.” I applied in 2019 and was accepted for 2020, but — my bad luck — it was postponed because of the pandemic. I began studying virtually in January and will be on campus in Lincoln for one and a half years. I’m studying integrated media and communication in the College of Journalism and Mass Communications.

Will you ever return to Afghanistan?

At this point, if someone said I’m going back, I’d say ‘It’s too dangerous for me, I will not be alive.’ But if something magic happens, if there is a democratic system again, I will go. I have plans there. I have a life there. This country doesn’t need me. In my country, I can serve. One and a half years is a lot of time. Maybe things will change.