· 5 min read

Science fuels Lai’s fascination with fireworks

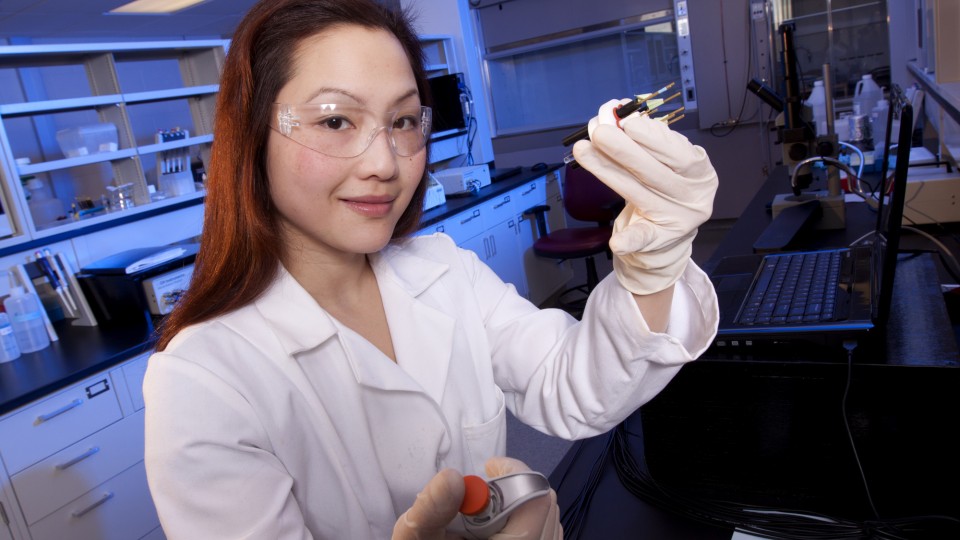

Rebecca Lai can't wait to see little booms and bursts of science lighting up the skyline each July 4.

Lai's fascination with fireworks sparked when she was about 5 as she watched Chinese New Year celebrations blast away over Victoria Harbor in Hong Kong. And, though the Susan J. Rosowski Associate Professor of Chemistry is well versed in the science behind fireworks, she still gets a thrill out of watching annual pyrotechnic displays.

"I've always liked fireworks, from lighting and watching them to learning about the history and science behind them," Lai said.

Lai has incorporated some of the history and science behind fireworks into "A Muggle's Guide to Harry Potter's Chemistry" (CHEM 192H), an undergraduate course she created at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Along with teaching, she also serves as a researcher and is graduate admissions chair for the Department of Chemistry.

Lai's research is focused on the development of electrochemical biosensors. The work has led to a series of metal-detecting sensors, including one that can sense gold. A primary purpose for the sensors would be to detect water contaminants.

While fireworks in the Harry Potter tales are more magical, Lai focuses on the chemicals used to create color in fireworks and how ninth-century alchemists in China created gunpowder while searching for an elixir of life.

"They sought a mixture of immortality and started experimenting with potassium nitrate,” she said. "Ironically, they ended up was an elixir of mortality because it explodes when heated up."

Chinese called the black powder "huo yao" (fire chemical), developing the first firecrackers out of bamboo sticks. The firecrackers played an essential role in Chinese festivities, including weddings and religious rituals, due to the belief that the bang was powerful enough to scare off evil spirits. By 1046, the Chinese were using gunpowder in warfare.

English scholar Roger Bacon (1214-1294) was one of the first Europeans to study gunpowder. He realized Salt Peter was the driving force behind the explosive power of gunpowder. Because of gunpowder's dangerous potential, Bacon wrote his findings in a code that was not deciphered for hundreds of years.

In 1560, European chemists developed a gunpowder mix that is still being used today. Its development brought an end to Medieval warfare as it allowed for projectiles that could pierce metal armor and blow apart castle walls.

Credit for the development of gunpowder into aerial shell fireworks that produce fountains of color in the sky is given to the Italians.

For nearly 2,000 years, the only colors fireworks could produce were yellows and oranges using steel and charcoal. In the 19th century, technology allowed for reds, greens and blues to light up the sky.

"Learning about the different chemicals used to create the colors is something I really enjoyed," Lai said. "If you want red, you use strontium. Green is barium. And for purple, they mix copper and strontium compounds.

"Then they mix in gunpowder as fuel, oxidizers to help with combustion, chlorine compounds to enhance colors and binders to hold it all together. When used properly, they really are wonderful little scientific creations."

Lai plans to offer the Harry Potter course again and is developing a lab component for what was just a lecture course. One lab project would involve creating red and green "magic wand" sparklers from chemicals and wooden sticks.

Lai will also integrate elements of the Harry Potter class into a seven-week after-school program she is offering at Lincoln Public Schools' Kloefkorn Elementary School.

"We'll cover a different book each week," Lai said. "The goal is to showcase elements of chemistry that are related to the books. We will definitely talk about fireworks, but we won't be making them or lighting them."

Chemistry of Fireworks

The colors in fireworks are created by pyrotechnic bursts. Those bursts contain five basic ingredients:

Color-producing compounds — Specific compounds produce intense colors when burned. Generally, these compounds are metal salts. Watch the animated gif above to review compounds that generate specific colors.

Fuel — Allows the fireworks to burn. Gunpowder, a mix of potassium nitrate, sulfur and charcoal, is most often used.

Oxidizer — Compound that provides oxygen to fuel combustion. Most likely nitrates, chlorates or perchlorates.

Binder — Holds the chemical mixture together. The most common binder is a mix of dextrin (starch) and water.

Chlorine donor — Help strengthen some colors. In some firework mixtures, the oxidizer can act as a chlorine donor.