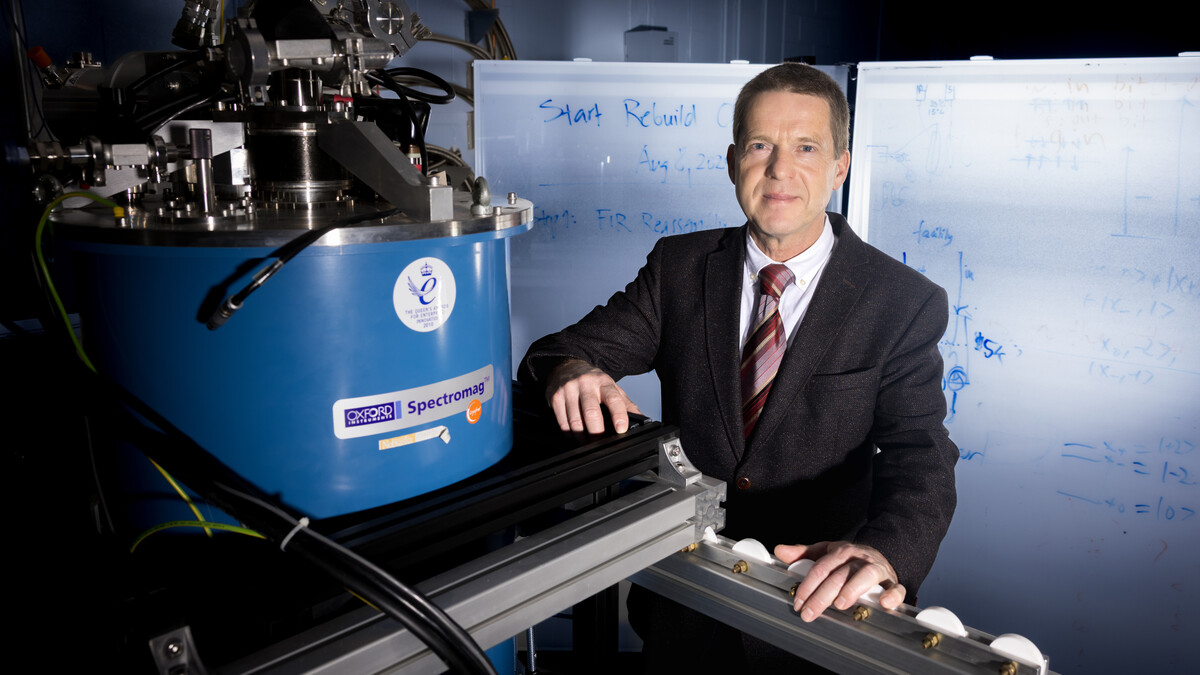

University of Nebraska tax law professor Adam Thimmesch is among more than 7 million people who have downloaded the phenomenally popular Pokémon Go game application since its July 6 release.

Admittedly, Thimmesch has only made it to level four. His children are calling for him to play more often to improve his performance during Pokémon battles.

Yet as a scholar who specializes in the ways new technology affects the legal system, Thimmesch says the game raises fascinating questions that will give law buffs lots to talk about — at least for as long as the fad lasts.

Not all of those questions will be answered in a courtroom — for one thing, users must agree to resolve most disputes through arbitration even before they can download the app. For another, Thimmesch predicts Pokémon Go and other augmented reality games will lead to new social norms governing behavior in digital reality.

Following are some of his observations about how the game might intersect with the law.

Pokémon Go is not just another smartphone game

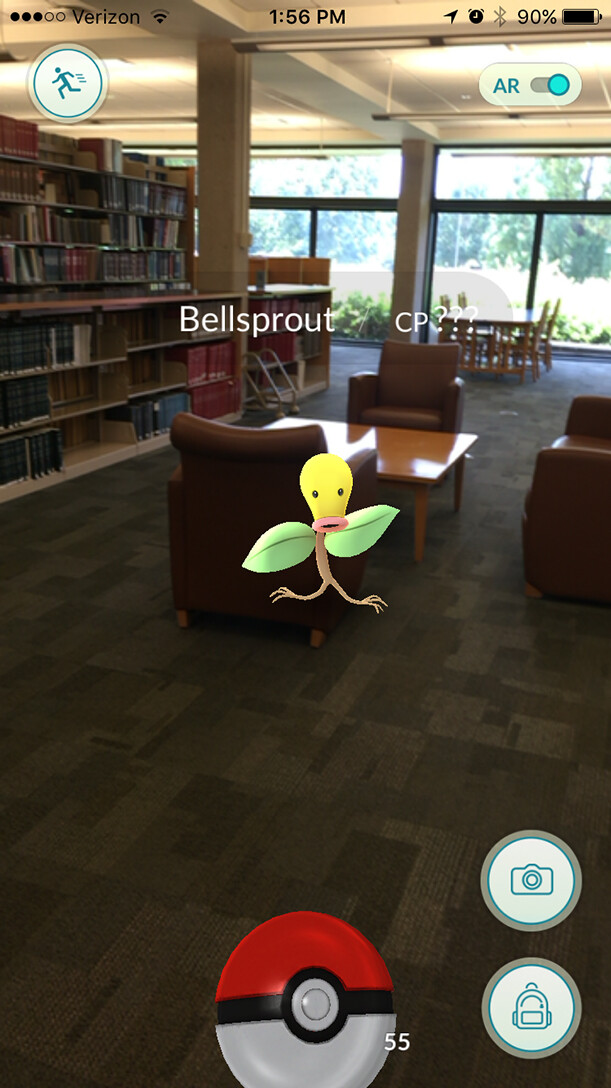

What makes Pokémon Go different from other popular game apps is its successful use of augmented reality to place digital attractions like Pokémon, Pokéstops, and Pokémon Gyms at real world locations.

That aspect has caused problems, with users getting hurt or causing traffic accidents. Some users have stumbled upon dead bodies, while others have prompted police calls.

“Pokémon Go not only takes users out into the real world, but it brings real world issues into the gaming world,” Thimmesch said. “As with any other new technology, this causes some tension—both with how existing laws apply to that technology and at how the technology might change existing law.”

Real world rights and responsibilities still apply in the Pokémon Go universe

Even if a Pikachu happens to “appear” on their lawn, property owners still have a right to keep others off their property. Gamers who walk onto private property in the quest to “catch ‘em all” can face charges for trespass.

Negligence laws could hold Pokémon Go trainers liable for damages and injuries if the game distracts them while they are driving, riding, or walking and playing. Some legal experts question whether the application’s developers might also be held liable in such cases.

Criminal sanctions also could be possible, for trespassing, for traffic violations, or even for real world fights that might break out over a Pokémon battle.

Thimmesch urges users to abide by limits set by property owners of locations — like UNL’s Memorial Stadium — who provide users with special access for Pokémon hunting.

“The bottom line is to think and be careful,” Thimmesch said. “Claiming that you were distracted by a Pokémon alert will not provide a defense.”

Augmented-reality gaming like Pokémon Go poses many unanswered questions

Does a property owner have a right to the Rhyhorn that a user collects while trespassing? Can the game developer be sued if a digital object disrupts someone’s business? Do some locations, like the Holocaust Museum, have the right to opt out of the game? Can the game be restricted on public property?

Under the terms of service, users have only a limited right to their Pokémon. They do not obtain any property rights in those digital assets, and they cannot be sold, transferred, or exchanged for other Pokémon Go assets, for money, for services, or any other consideration. Those limitations apply equally to items purchased in the application, such as Pokéballs, incense, lucky eggs, or Pokécoins. The developer can cancel, suspend, or terminate a user’s account without refunds.

“Invest in, and develop, your Pokémon at your own risk!” Thimmesch said.

U.S. law does little to protect users’ privacy

To download the Pokémon Go app, users agree to a wide range of permissions that may give the game developer access to potentially significant information — not only GPS location data required to play the game, but also possibly Gmail accounts and other sensitive personal information.

Although public pressure may lead developers to change the permissions required for the game, there is no guarantee that developers of future games will take a similar approach.

“A company can essentially collect whatever information it requests, as long as you hit “accept” and download the application,” Thimmesch said. “ The law is of little help in this regard.”

Taxing Pokémon Go.

Even though the app includes no Poké tax collector, the game does have real-world tax implications.

Games like Pokémon Go will only increase the stress digital commerce places on outdated state tax systems. A customer who purchases a toy Pokéball in a store would generally pay state sales tax on that purchase, but she might not pay that tax on a digital version purchased through the Pokémon Go app. Some states may already require sales tax on Pokémon Go purchases, or they might start doing so.

The rise of digital assets also gives companies greater ability to shift profits offshore and to reduce their U.S. income tax payments.

At a more theoretical level, tax scholars have long wondered whether and how the receipt and use of in-game digital assets should be taxed. This started with games like Second Life and World of Warcraft, but could now come to include games like Pokémon Go. The scenarios become even more intriguing when applications use a “freemium model” where uses get applications for free, but can buy in-app upgrades such as more Pokéballs.

“Could we see a world where getting free Pokéballs at a Pokéstop is a taxable event?” Thimmesch asked rhetorically. “Should we recognize that individual Pokémon trainers are really working for Nintendo by providing them endless streams of data?”

“The success of Pokémon Go will only create further incentive for developers to create this type of game, and users and the legal system will need to adapt,” he said. “In the meantime, good luck filling your Pokédex!”