· 3 min read

Gardner digitizing parasite samples for scientists everywhere

Data about tiny parasites, whether collected more than a century ago in Bolivia or last week in the Galapagos, play a key role in tracking biodiversity and disease globally. A Nebraska researcher is making it easier for scientists worldwide to access this information.

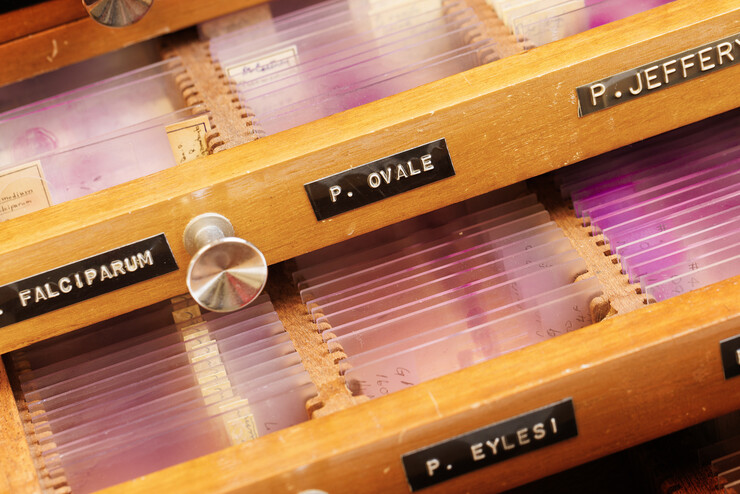

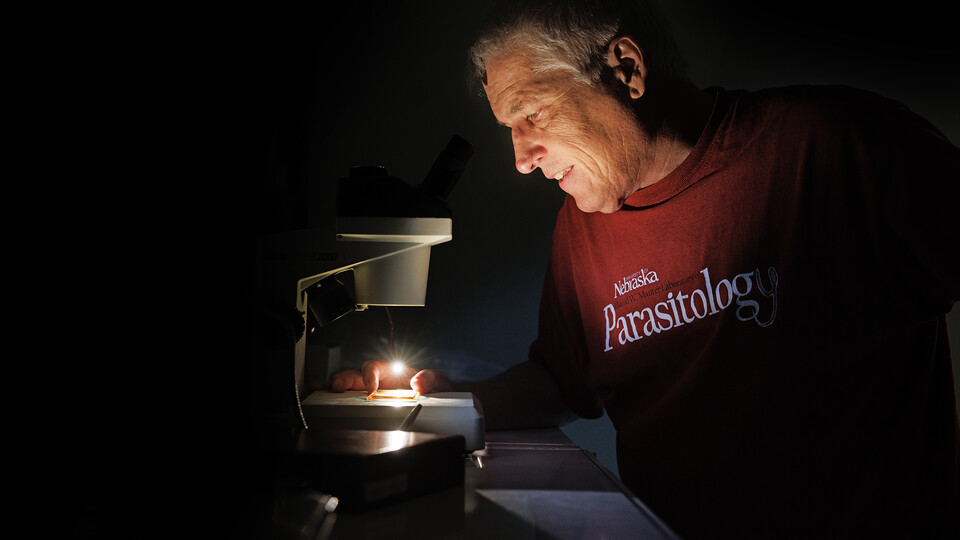

Scott L. Gardner, curator of parasitology for the University of Nebraska State Museum, has hundreds of thousands of parasite samples at his fingertips — mites, ticks, lice, fleas, tapeworms, trematodes and more. They’re on slides in cabinets, in vials of ethanol, in tubes in ultra-low temperature freezers — and now some are available via online database.

The museum’s Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology houses the second-largest collection of parasite samples in the Western Hemisphere, eclipsed only by the holdings of the Smithsonian Institution. Nebraska’s collection includes samples from all continents and oceans, is continuing to acquire individual researchers’ collections and is a critical resource for scientists everywhere.

Two National Science Foundation grants — totaling more than $900,000 — have partially funded digitization of the lab’s collection. Specimen data and actual images of the parasites have been uploaded to the Arctos database, a collection management system for natural and cultural history museums and collections.

“We make sure that specimens that are collected are kept in the best condition for the use of people to document biodiversity in the world,” said Gardner, also a professor of biological sciences.

Discovering new parasites and tracking where known ones show up helps scientists understand diseases of both humans and animals, Gardner said. To address this critical need, parasitologists gathered in 2012 at the Cedar Point Biological Station in Nebraska and developed a cooperative protocol for sharing and acting on essential information about the evolution, ecology and epidemiology of parasites across host groups, parasite groups, geographical regions and ecosystems.

The resulting plan helps scientists understand, anticipate and respond to the impact of accelerated environmental change on parasite distribution. The DAMA protocol has now been implemented a couple of times — once to devise a plan to stop transmission of Lyme disease in Hungary.

Providing scientists access to data about parasites will be key to efforts to predict their paths and fight the diseases they cause in the future, Gardner said.

This story was included in the Office of Research and Economic Development’s annual report. View the full report here.